PART 1: A work exploring notes and ideas on the nature of consciousness

The human quest to understand consciousness is as fascinating as it is frustrating. Consciousness – that elusive, essential aspect of our humanity – has captivated philosophers, neurologists, and psychologists for centuries. Yet, pinning down its history is a slippery business. The problem? Consciousness is woven from countless threads – biological, psychological, social – making it devilishly hard to trace its evolution. Still, to grasp this enigma, we must begin with the basics.

Let’s start with the word itself. ‘Conscious’ stems from the Latin ‘cum’ (together) and ‘scire’ (knowing). Originally, consciousness referred to shared knowledge – two people aware of something together. Fast forward to modern times, and we find a split in definitions:

* Neurology: Consciousness is a physical and mental state – being awake, aware, alert, and in control of your brain and senses.

* Psychology: Consciousness is awareness of self and surroundings, a sense of individuality that separates ‘I’ from the world.

Notice the common thread? Knowing. Awareness. But awareness of what, exactly? René Descartes, the famous philosopher, declared, “I think, therefore I am.” He was the first to spotlight self-awareness, but is thought alone enough to constitute consciousness? This question has haunted researchers for years, leading many – myself included – to explore the ties between consciousness, language, and society. And here’s where things get tricky.

My observations suggest that consciousness isn’t just in the mind, but in the reality we construct collectively. This makes mapping a ‘history’ of consciousness a bit of a misnomer. I don’t believe there’s a clear-cut timeline so much as an ongoing evolution. And that’s where our journey gets really interesting.

The Ever-Changing Tapestry of Consciousness

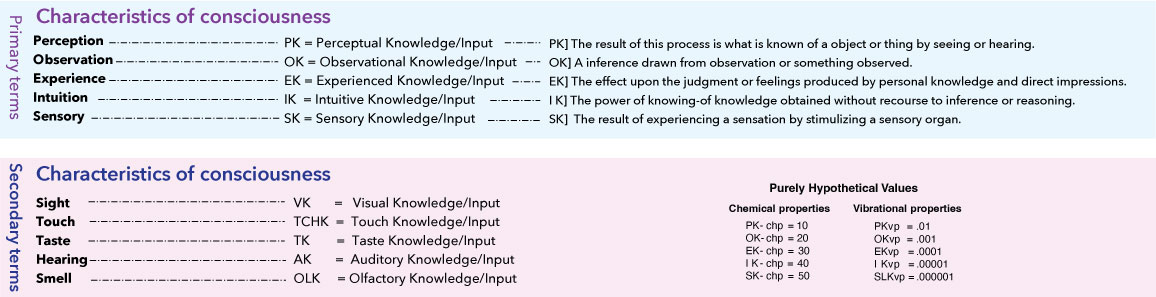

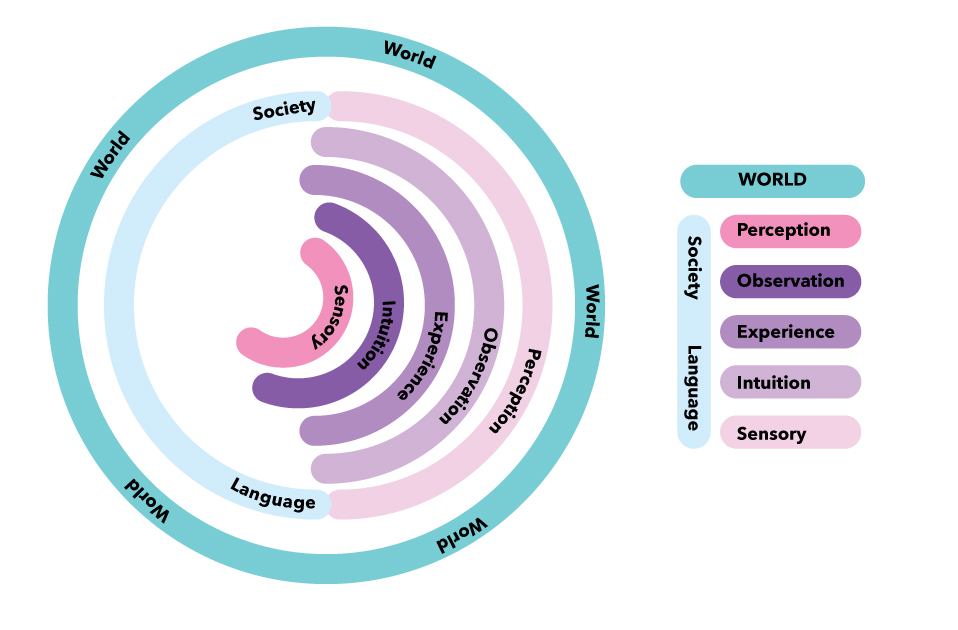

Consciousness is a dynamic interplay of factors, all subject to the forces of evolution and change. Picture a complex network, with components like those listed in Figure 1 influencing its shape and function. This system is constantly adapting, molded by the ebb and flow of environmental stimuli, including the powerful influence of culture.

At the heart of consciousness lies its reflective nature. It not only responds to the external world but also plays an active role in shaping the environment in which it operates. This ongoing interplay gives rise to the sense of a evolving “history” or “story” of consciousness.

Jean Piaget’s groundbreaking work on cognitive development offers valuable insights into this evolution. His stages of development, outlined in his theory of Genetic Epistemology, illuminate the growth of conscious awareness from infancy to adolescence.

The journey begins with the Sensorimotor stage (0-2 years), where infants discover their existence as separate beings through experimentation and mastery of their surroundings. Language blossoms during the Preoperational stage (2-7 years), opening up new avenues for thought and understanding. As children enter the Concrete Operational stage (7-12 years), they learn to classify objects based on their similarities and differences. The final Formal Operational stage is reached when adolescents can manipulate abstract ideas and consider multiple perspectives.

Piaget’s stages offer a fascinating glimpse into the construction of the conscious mind. Even his earliest stage highlights the critical moment when a sense of self first emerges.

Consciousness is not a mystical entity, but rather a natural process, subject to the same physical principles as the rest of the universe. It has a structure, a tangible presence in the workings of the brain. This idea forms the foundation of Biogenetic Structuralism, which seeks to understand consciousness as an organic, evolving system intertwined with the physical world.

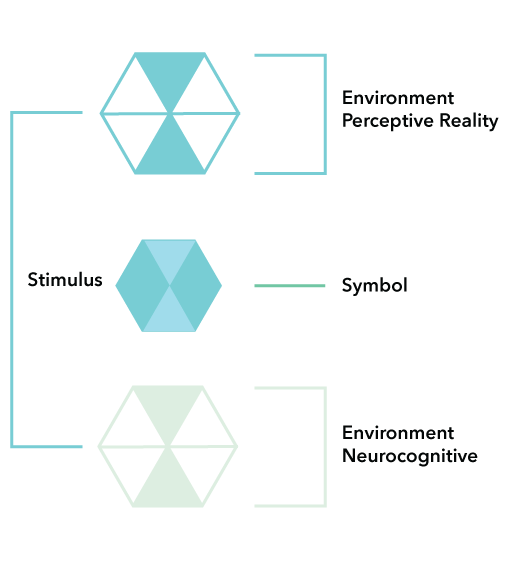

Which has occurred first the cognized environment or the perceptive reality ? If the stimulus exist in both simultaneously .

Biogenetic structuralism

Imagine this bold idea: the only reality that exists lies directly between your brain and the world around you. That’s the foundation of biogenetic structuralism. It means that concepts like “mind,” “personality,” “culture,” and “society” aren’t separate realities – they’re just patterns we’ve abstracted from how our brains interact with our environment.

This perspective asserts that the “mind” and the “brain” are two sides of the same coin. The mind is simply your brain’s experience of its own function. Your brain is the structure, and your mind is what emerges from it.

Charles Laughlin, John McManus, and Eugene d’Aquili have done groundbreaking work on how this plays out in our experience of consciousness and symbols. Once you accept that the mind and brain are different views of the same thing, you’re left with a fascinating question: how does our brain develop its sense of self in response to the world?

The answer seems to be that our consciousness is shaped by our interactions with our environment from the very beginning. Think about it – our entire sense of self emerges from the stimuli we’re exposed to. So, which comes first, the self or the environment? It’s a chicken-and-egg problem, but biogenetic structuralism gives us a framework to explore it in a new way.

This theory pulls together insights from anthropology and neuroscience to create a more integrated understanding of human experience. It’s a mind-blowing perspective that could change how we think about everything from personality to culture to society. The more we learn, the more we realize that our minds aren’t isolated entities – they’re constantly interacting with and shaped by the world around us.

Vygotsky’s Insights: Social Interaction and Cognitive Development

The work of L.S. Vygotsky offers intriguing validation of the themes presented here. A central idea in Vygotsky’s work is that social interaction is crucial for the development of our cognitive abilities. As he puts it:

Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (inter-psychological) and then inside the child (intra-psychological). This applies equally to voluntary attention, to logical memory, and to the formation of concepts. All the higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals.

(Vygotsky, L.S. [1978]. Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.)

While the exact role of social interaction in cognitive development is open to debate, its importance is undeniable. This leads me to propose a new hypothesis, which I call the “Piano Theory,” to help understand this development.

The Piano Theory: A Framework for Understanding Cognitive Development

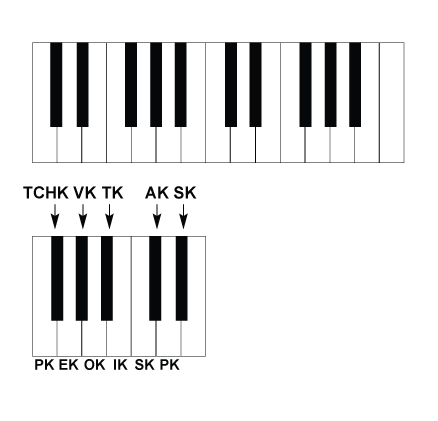

The Piano Theory draws on what we currently know about perception, information assimilation, and memory retention following interaction or observation. Imagine the piano as a model for our thought processes. A key observation is that the piano exists independently of any stimulus – i.e., consciousness exists outside of language. We can make sounds on the piano without knowing how to read music, demonstrating that consciousness precedes developed language.

Now, let’s imagine being locked in a room with a piano for several years. At first, we’d experiment with the keys, establishing the initial codes of our conscious network (the phonetic and alphabetic aspects of language). Over time, we’d create more complex sound systems by playing multiple notes together, establishing chord structures, etc. Meaning, emotions, and conceptual hierarchies would become associated with the sounds. From these foundational systems, more complex systems would emerge, enabling multiple meanings, associations, and alternative structures like emotional and logical patterns.

The piano analogy is useful because it’s sensitive to touch and its sounds are regulated by vibration (e.g., 440, 220, 180 Hz). Establishing this foundational understanding is crucial for studying neurological functions, cognition, consciousness, and higher-order functions like language, logic, and altered states of consciousness.

Reflection and Future Directions

While the Piano Theory is speculative, it offers a compelling framework for visualizing how our cognitive abilities might develop from initial awareness to complex systems. It highlights the importance of experimentation, social interaction, and the creation of meaning for cognitive development. Future research could explore this model in more depth, considering how it aligns with existing knowledge and suggesting new avenues for investigation.

The Theory

Picture the brain as the very essence of consciousness, a dazzling tapestry woven from countless, interconnected threads. These threads represent various aspects of our awareness, each one influencing and informing the others. As we delve deeper into the brain’s mysteries, we uncover intricate networks of neurons, sprawling and expanding in a dance that mirrors the asymmetrical world around us.

The Elements

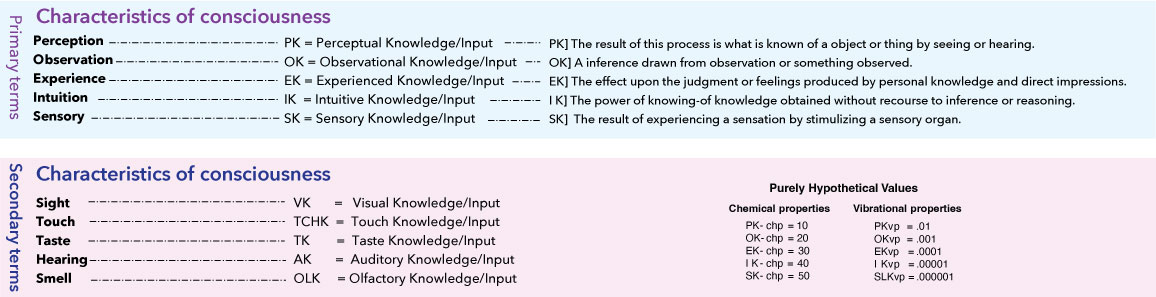

It is my belief that consciousness is organized as any other formal system, on the previous pageI have broken down what I consider to be the primary and secondary elements relating to the fundamental operations of consciousness. At this time I will introduce the concept of parcepts and cocepts.

Cocept

\ kö\ \cep\-t

Ko ) 1 . meaning — together with.- a prefix of c o m-,

2) a stated value separated ; separate

Cocepts are the individual elements that construct parcepts they are comprised of information based on the individual input of sensory and perceptual information.

Parcept

\ pär\ \cep\-t

Par ) a common level

2) a stated value separated ; separate

Parcepts are the combined elements of individual cocepts organized to form fundamental stages of experiences as they relate to cognitive processes [ thinking/ knowledge ].

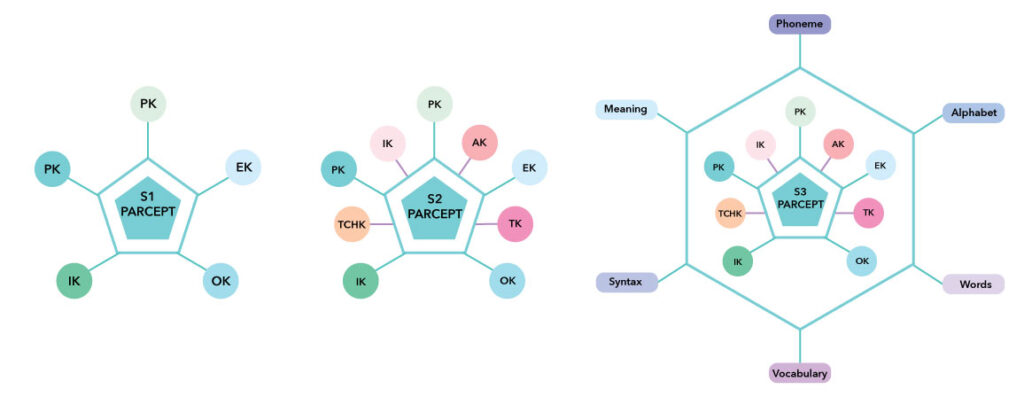

The combination of cocepts into parcepts with the addition of other rudimentary elements such as language etc…. come to form what I refer to as stages. In the following illustrations I have drawn what each of the possible combinations would look like. These structures are what I believe to be the foundation of consciousness.

Fig 5 These units I shall refer to as parcepts, each parcept contains 5 cocepts of information these units shall be referred to as stages this is a “Stage 1 parcept”it is the simplest breakdown in this system.

Fig 6 In figure 6 we see the addition of secondary definitions which consist primarily of sensory information. This configuration will be referred to as a “Stage 2 parcept”

Fig 7 In figure 7 we see the addition of the separate constructs of language this shall be known as a “Stage 3 parcept”

Fig 5

Fig 6

Fig 7